The Federal Government announced this week that, contrary to previous advice, they will not change the form for the 2026 National Census to enable recognition of LGBTIQ+ members of the population. The Australian Bureau of Statistics issued a formal apology after the 2021 Census when it was revealed that many LGBTIQ+ people were not counted in the census because it did not include questions on gender identity and sexual orientation. A working party was established to investigate and propose new questions for inclusion in the 2026 Census, and the Federal Government anticipated re-shaping the census form accordingly. Much to the chagrin of the LGBTIQ+ community and others, it has now stepped back from that intention. I recently signed the Equality Australia ‘Count Us In’ petition, in the hope that the government may yet agree to edit the form. But my primary question at this point is ‘Why this change of heart?’ Surely the inclusion of these questions would be affirming of the LGBTIQ+ community and provide useful data for future planning and service delivery. So why not collect it? Why has the government reneged on its initial intention?

To this point, the government has provided no rationale for its decision, with the Assistant Minister for Treasury, Andrew Lee, confirming in an interview with the ABC that the choice not to change topics is the decision of the government, but giving no justification for it.[1]

It leads me to wonder what ‘influencers’ or lobby groups are at play in this process. Is the decision a reflection of the creeping conservatism that appears to be impacting governments around the world, or are there some particular voices or interests whispering in government ears? I have no evidence, of course, but I am concerned that pressure (real or anticipated) from conservative Christian groups, like the Australian Christian Lobby, is unduly influencing government decision-making. One of the ACL’s current campaigns is headed ‘The Truth Behind the Gender Agenda’ so it is certainly on their radar. Why does this concern me? Well, not because of the lobbying per se – everyone has a right to lobby appropriately for their voices and opinions to be heard by parliament – but rather because the ACL purports to represent the Christian Church, when in fact it represents just a segment of it. In so many of its policies, platforms and press releases the ACL does not represent me. So, it is a concern if the government places more weight than is warranted on the opinions and attitudes of groups like the Australian Christian Lobby.

And it begs a broader question. How is it that the Christian Church has become known more for what it’s against than what it’s for; more for its ‘thou shalt not’ than its ‘do this’; more for its judgement than its grace; more for its rules than its love. How did that happen? How did a faith system founded on the values of justice and love, a faith system intended to be life-giving, end up being so apparently life-denying?

Here’s my radical theory: Good Friday is the problem! Or, more accurately, the Church’s unhealthy fixation on Good Friday and its themes of sacrifice, atonement, judgement, and death is the problem. I mean, the early Christian Church so idealised – even idolised – Good Friday that they adopted its cruel and gruesome emblem, the cross, as their logo! It ought not surprise us that an organisation gathered around such a symbol would move, over time, in the direction of piety and solemnity, of negativity and constraint. And before long, we find ourselves worshipping the motifs of sacrifice, self-deprivation and self-deprecation, formulating an overly legalistic system to order our life and shape our culture. Law before grace, rules before love. I may be over-stating the situation, but I do think that an over-emphasis on Good Friday – on the crucifixion and death of Jesus – has created a religious culture that is too-often negative and legalistic.

The movie Babette’s Feast illustrates this eternal ecclesial tension. Babette, a French housemaid, has settled in a Puritan village and prepares a banquet for the villagers to say thank you to them for welcoming her to their community. The villagers are horrified at the extravagance, the indulgence of the feast, but they accept her invitation, not wanting to offend her or to demean her generosity. But in good Puritan tradition, while they agree to attend the banquet, they also agree that they will not allow themselves to enjoy it! What a great caricature of so much of our Christian religious history!

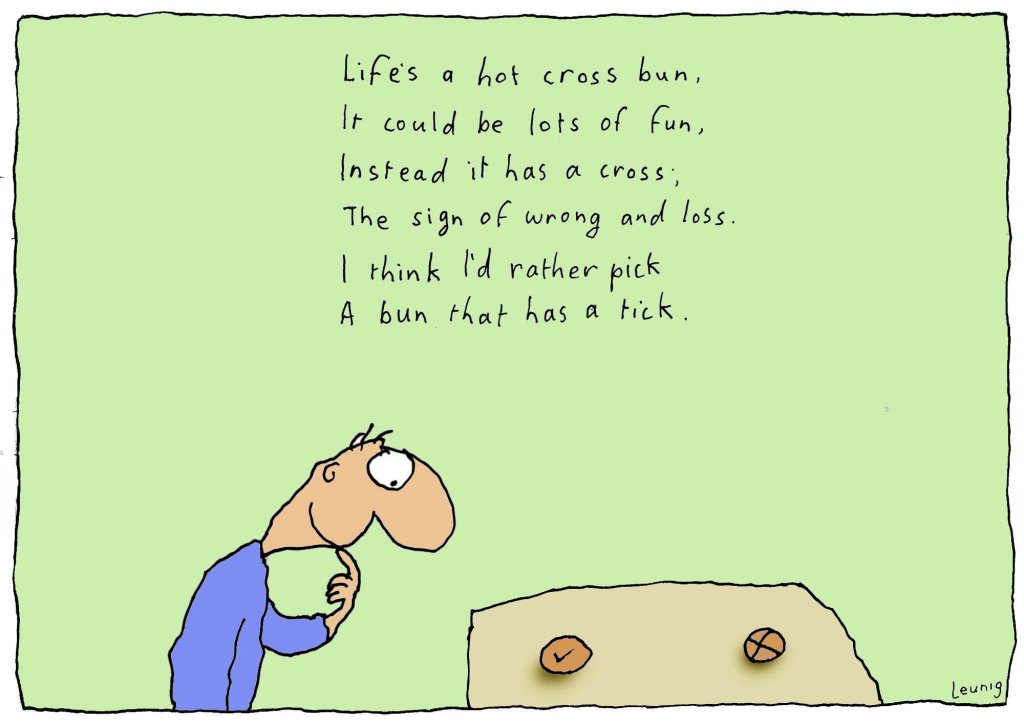

Michael Leunig has also captured the tension in this out-of-season but on-topic cartoon:

It’s a pertinent question: instead of a cross that implies not only ‘wrong and loss’ but denial and judgement, why not a tick that implies ‘yes’, that implies affirmation, liberty and life?

How come a cross became the symbol of the Christian Church rather than an empty tomb or a tick? Why is Good Friday the ‘holiest’ public holiday, the day when all the shops are closed, and not Easter Day, the day of resurrection and new life? Why are the motifs of denial and death more prominent in the church then those of life and delight? Why isn’t the Christian Church known more for its grace than its Law? More for its love than its rules?

A Christian Church focussed on a cross is likely to choose a more constrictive and negative pathway, drawing boundaries and defining limits, and perhaps even lobbying against the affirmation and inclusion of those whose gender identity differs from theirs. A Christian Church focussed a tick, might proclaim freedom and affirm diversity and champion the affirmation and inclusion of people of diverse gender identities – in their communities and in the National Census.

Grace not Law, love not rules! Which Easter bun would you choose?

David Brooker

28th August 2024

[1] ABC Listen, 26th August 2024

Leave a comment